For 'Under the Dome,' 'a season of transformation'

Changes in the Dome cause Chester's Mill residents to collapse just as Big Jim Rennie (Dean Norris), to the right on the scaffolding, plans to hang Dale "Barbie" Barbara (Mike Vogel). "Along with the bright light, there's something transformative happening where the Dome is maybe not so happy with what's going on," executive producer Baer says.

Big Jim Rennie (Dean Norris) pleads with the Dome as he kneels over the motionless body of his son, Junior (Alexander Koch). "Big Jim has done some pretty heinous things," executive producer Baer says. "Now, it's Judgment Day."

Life is only going to get more intense Under the Dome.

Residents of Chester's Mill, trapped under a clear dome that turned black before emitting a blinding light in the first-season finale, will face more of its effects — causing some to collapse — when Season 2 opens (CBS, June 30, 10 p.m. ET/PT).

"This is a season of transformation," executive producer Neal Baer says. "Last year was a season of secrets being revealed about our characters. Now, they really have to cope with the ramifications of what this all means, since it doesn't look like they're getting out any time soon."

Dome, based on Stephen King's novel of the same name, was the most-watched scripted summer series in 21 years, averaging 15.1 million viewers, and performed strongly internationally. King wrote the second season's first episode, Heads Will Roll, and will be seen in a cameo appearance in the town's diner.

"It was fantastic to work directly with Stephen. He's been a real hero of mine and now I get to work with him," Baer says. In the cameo, the author, who has made brief appearances in other adapted works, "is just a citizen of Chester's Mill for at least the moment."

Two familiar characters will die in the opener of Dome, which is going beyond King's book. However, the series also will add new people: Sam Verdreaux (Eddie Cahill), a reclusive man who is the brother-in-law of Big Jim Rennie (Dean Norris); Rebecca Pine (Karla Crome), a teacher who works with Big Jim and brings a science perspective; and Melanie (Grace Victoria Cox), a character pulled from the lake by Julia Shumway (Rachelle Lefevre) just after she throws the mysterious egg into the water at the end of the first-season finale.

Julia bonds with both Melanie and Sam, who "seems to be a good ally," although the latter connection could influence her relationship with Dale "Barbie" Barbara (Mike Vogel), Lefevre says. After she saves Melanie, "she becomes completely invested in her."

Julia must also adapt to a leadership role after the Dome appears to tap her as "the monarch."

"Someone has to lead (but) how do you decide who that is?"

Should Pregnant Women Risk Mood Meds?

Until the 30th week, Suzanne Sevlie's second pregnancy

had been progressing well and she was happy and healthy. But in the

final weeks of her pregnancy, a close friend's death left Sevlie depressed and frustrated with her inability to connect with her unborn child.

"I thought I just don't feel right. I don't feel like I'm happy," Sevlie

said. "There was a point where I literally felt like I wanted to cut my

stomach out because I was so detached from the baby at that point."

Sevlie had experienced depression once before when she was 15, for which

she received medication and counseling. But after high school and

through her first pregnancy at age 23, Sevlie had no mental health

issues. Her depression during her second pregnancy was a development she

would not accept.

"I didn't take [medication] when I was pregnant because I didn't know

there were any options," said Sevlie, whose obstetrician recommended

monitoring when she told him how she felt. "I knew once the baby came I

could do that if I wanted to... But I knew that if it got out of control

it could have an effect on the baby and my family. I thought: this is

not happening!"

Having depression during pregnancy puts everyone, from parents to

clinicians, in a precarious position. Depression can be harmful to a

mother and her developing baby. But taking antidepressants also pose

risks since a fetus can be affected by any substance a mother introduces

to her body.

Fresh Guidance For Pregnant Women With Depression

Past guidance on depression during pregnancy has been mixed, with

obstetricians and psychiatrists often offering conflicting advice on

management. But a new report that combines recommendations from

obstetricians and psychiatrists may mean that women are poised to

receive better prenatal mental health care.

Today, the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists released a collaborative report

that sums up past research and is the first to offer concrete

guidelines for treating depression in pregnant women. The report was

co-published in the journals Obstetrics and Gynecology and General

Hospital Psychiatry.

"[The report] is an excellent synthesis of what is known in the

literature to date about the risks of both mood disorders during

pregnancy and the risks of using antidepressants," said Sheryl

Kingsberg, chief of the Division of Behavioral Medicine at University

Hospitals Case Medical Center. "The basic guidelines have been to make

the decision on an individual basis and to recognize that non-treatment

of depression is not benign. I think it provides the 2009 update that

has been needed."

Depression During Pregnancy Can Be a Major Problem

Between 14 and 23 percent of pregnant women experience depression during pregnancy and, as of 2003, 13 percent of pregnant women took antidepressants to combat the illness.

Based on criteria such as the severity of depressive symptoms, past

success with psychotherapy and the patient's desire to be on medication,

the report provided guidance on evaluation and treatment options for

women with depression who wish to conceive or who are already pregnant.

Should Pregnant Women Risk Mood Meds?

For instance, the report advises that it is safe for some women to taper

off medication before or during pregnancy if their symptoms are mild

and they respond well to psychotherapy. In women with a history of

severe, recurrent depression, however, or those with suicidal symptoms,

refraining from medication is not advised as they may become a danger to

themselves and their baby.

"There are a lot of people who don't know this information," said Dr.

Sudeepta Varma, a psychiatrist at the New York University Medical

Center. "It might come as a surprise to some that it's necessary to

treat patients [with drugs] when they're pregnant. I think there are

clinicians that shy away from it."

Risks Of Depression May Outweight The Risks Of Medication

Though the prenatal risks of taking antidepressants are not fully known,

the report stresses the potential negative impact of allowing

depression to go untreated as a mitigating factor in the decision to

medicate.

Depressed mothers are at increased risk of substance abuse, of poor

compliance with prenatal care, and have poorer nutritional habits than

mothers who are not depressed.

"You cannot separate the needs of the mother from the needs of her

fetus," said Dr. Lucy Puryear, a reproductive psychiatrist and author of

the book Understanding Your Moods When Your Expecting: Emotions, Mental

Health, and Happiness—Before, During, and After Pregnancy. "To ignore

the pregnant woman's mental health in order to 'protect' her baby causes

distress to the pregnant mother and her family."

Some Oppose Antidepressant Use

Dr. Kimberly Yonkers, a psychiatrist at the Yale School of Medicine and

lead author of the report, said there have been "a number of scares"

regarding taking antidepressants during pregnancy.

"The majority of the literature has looked at the effects of depression

on pregnancy... or looked at the effect of medication on pregnancy

without considering the effect of the depressive symptoms themselves,"

she added.

But while some clinicians may sidestep the issue, certain groups

strongly oppose using antidepressant medications during pregnancy.

"We're not in favor of women taking [antidepressants] when they're

pregnant," said Amy Philo, co-founder of Children and Adults Against

Drugging America (CHAADA) and momsandmeds.com. "I don't know how people

can logically believe that feeling sad when you're pregnant is going to

cause [complications]."

Philo, who said she experienced suicidal and homicidal thoughts after

being preemptively prescribed an antidepressant for post-partum

depression, cited cardiac problems, fetal abnormalities, Sudden Infant

Death Syndrome, and intra-uterine or neonatal death as potential risk

factors of drug therapy.

"Definitely [antidepressants] can hurt the baby," Philo said. "We

encourage people to get all the information that's out there and find

support that is not drug oriented."

Evidence Against Antidepressant Use Is Not Compelling

But Dr. Ruta Nonacs, a psychiatrist with the Perinatal and Reproductive

Psychiatry Clinical Research Program at Massachusetts General Hospital,

said there is no scientific data to support that treating mothers with

antidepressants leads to an increased risk of fetal abnormalities or

death.

"I don't think there's some smoking gun out there that's been hidden,"

Nonacs said, adding that misinformation, fear and personal preference

not to use drugs may be factors in deciding whether to use

antidepressants. "It's a reasonable fear of harming kids which probably

everybody has... that's gone awry."

Depression Can Lead to Lost Time With Children

And Sevlie pointed out that her experience with untreated depression

during pregnancy as well as the eight months of post-partum depression

she endured -- for which she did complete a course of treatment -- led

to feeling alienated from her daughter.

"I feel like I lost that first year of her life," Sevlie said. "I don't

remember when her teeth came in or when she sat up... I remember feeling

I wasn't the mom I was supposed to be."

Over the course of her pregnancy and subsequent treatment for

post-partum depression, Sevlie said her obstetrician and psychiatrist

may have shared her medical charts but that neither asked what the other

was advising her to do.

"I would have liked to know more of my options," Sevlie said. "Not just

medications but outlets for depression and pregnancy support."

Experts stressed that some facets of the report highlight the need for

more research on the risks of both depression and antidepressant

treatment. But unified recommendations from both obstetricians

psychiatrists should assist in more effective treatment for pregnant

women with depression.

In Deep

The dark and dangerous world of extreme cavers

Atanasio, a cliff-face opening in the Sierra de Juárez mountains of Oaxaca, Mexico. The mountains are home to the Chevé system, some eighty-five hundred feet deep—potentially the deepest cave in the world.

On his thirteenth day underground, when he’d come to the edge of the known world and was preparing to pass beyond it, Marcin Gala placed a call to the surface. He’d travelled more than three miles through the earth by then, over stalagmites and boulder fields, cave-ins and vaulting galleries. He’d spidered down waterfalls, inched along crumbling ledges, and bellied through tunnels so tight that his back touched the roof with every breath. Now he stood at the shore of a small, dark pool under a dome of sulfurous flowstone. He felt the weight of the mountain above him—a mile of solid rock—and wondered if he’d ever find his way back again. It was his last chance to hear his wife and daughter’s voices before the cave swallowed him up.

“Base camp, base camp, base camp,” he said.

“This is Camp Four. Over.” His voice travelled from the handset to a

Teflon-coated wire that he had strung along the wall. It wound its way

through sump and tunnel, up the stair-step passages of the Chevé system

to a ragged cleft in a hillside seven thousand feet above sea level.

There, in a cloud forest in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, lay the staging

area for an attempt to map the deepest cave in the world—a kind of

Everest expedition turned upside down. Gala’s voice fell soft and

muffled in the mountain’s belly, husky with fatigue. He asked his

seven-year-old, Zuzia, how she liked the Pippi Longstocking book she’d

been reading, and wondered what the weather was like on the surface.

Then the voice of Bill Stone, the leader of the expedition, broke over

the line. “We’re counting on you guys,” he said. “This is a big day. Do

your best, but don’t do anything radical. Be brave, but not too brave.”

Gala had been this deep in the cave once before, in 2009, but never beyond the pool. A baby-faced Pole of unremarkable physique—more plumber than mountaineer—he discovered caving as a young man in the Tatra Mountains, when they were one of the few places he could escape the strictures of Communism. When he was seventeen, he and another caver became the first people to climb, from top to bottom, what was then the world’s deepest cave, the Réseau Jean Bernard, in the French Alps. Now thirty-eight, he had explored caves throughout Europe and Ukraine, Hawaii, Central America, and New Guinea. In the off-season, he was a technician on a Norwegian oil platform, dangling high above the North Sea to weld joints and replace rivets. He was not easily unnerved. Then again Chevé was more than usually unnerving.

Caves are like living organisms, James Tabor wrote in “Blind Descent,” a book on Bill Stone’s earlier expeditions. They have bloodstreams and respiratory systems, infections and infestations. They take in organic matter and digest it, flushing it slowly through their systems. Chevé feels more alive than most. Its tunnels lie along an uneasy fault line in the Sierra de Juárez mountains and seethe with more than seven feet of rain a year. On his first trip to Mexico, in 2001, Gala nearly died of histoplasmosis, a fungal infection acquired from the bat guano that lined the upper reaches of a nearby cave. The local villagers had learned to steer clear of such places. They told stories of a malignant spirit that wandered Chevé’s tunnels, its feet pointing backward as it walked. When Western cavers first discovered the system, in 1986, they found some delicate white bones beneath a stone slab near the entrance: the remains of children probably sacrificed there hundreds of years ago by the Cuicatec people.

When the call to base camp was over, Gala hiked to the edge of the pool with his partner, the British cave diver Phil Short, and they put on their scuba rebreathers, masks, and fins. They’d spent the past two days on a platform suspended above another sump, rebuilding their gear. Many of the parts had been cracked or contaminated on the way down, so the two men took their time, cleaning each piece and cannibalizing components from an extra kit, knowing that they’d soon have no time to spare. The water here was between fifty and sixty degrees—cold enough to chill you within minutes—and Gala had no idea where the pool would lead. It might offer swift passage to the next shaft or lead into an endless, mud-dimmed labyrinth.

The rebreathers were good for four hours underwater, longer in a pinch. They removed carbon dioxide from a diver’s breath by passing it through cannisters of soda lime, then recirculating it back to the mouthpiece with a fresh puff of oxygen. Gala and Short were expert at managing dive time, but in the background another clock was always ticking. The team had arrived in February, three months before the rainy season. It was only mid-March now, but the weather wasn’t always predictable. In 2009, a flash flood had trapped two of Gala’s teammates in these tunnels for five days, unsure if the water would ever recede.

Gala had seen traces of its passage on the way down: old ropes shredded to fibre, phone lines stripped of insulation. When the heavy rain began to fall, it would flood this cave completely, trickling down from all over the mountain, gathering in ever-widening branches, dislodging boulders and carving new tunnels till it poured from the mountain into the Santo Domingo River. “You don’t want to be there when that happens,” Stone said. “There is no rescue, period.” To climb straight back to the surface, without stopping to rig ropes and phone wire, would take them four days. It took three days to get back from the moon.

Gala had been this deep in the cave once before, in 2009, but never beyond the pool. A baby-faced Pole of unremarkable physique—more plumber than mountaineer—he discovered caving as a young man in the Tatra Mountains, when they were one of the few places he could escape the strictures of Communism. When he was seventeen, he and another caver became the first people to climb, from top to bottom, what was then the world’s deepest cave, the Réseau Jean Bernard, in the French Alps. Now thirty-eight, he had explored caves throughout Europe and Ukraine, Hawaii, Central America, and New Guinea. In the off-season, he was a technician on a Norwegian oil platform, dangling high above the North Sea to weld joints and replace rivets. He was not easily unnerved. Then again Chevé was more than usually unnerving.

Caves are like living organisms, James Tabor wrote in “Blind Descent,” a book on Bill Stone’s earlier expeditions. They have bloodstreams and respiratory systems, infections and infestations. They take in organic matter and digest it, flushing it slowly through their systems. Chevé feels more alive than most. Its tunnels lie along an uneasy fault line in the Sierra de Juárez mountains and seethe with more than seven feet of rain a year. On his first trip to Mexico, in 2001, Gala nearly died of histoplasmosis, a fungal infection acquired from the bat guano that lined the upper reaches of a nearby cave. The local villagers had learned to steer clear of such places. They told stories of a malignant spirit that wandered Chevé’s tunnels, its feet pointing backward as it walked. When Western cavers first discovered the system, in 1986, they found some delicate white bones beneath a stone slab near the entrance: the remains of children probably sacrificed there hundreds of years ago by the Cuicatec people.

When the call to base camp was over, Gala hiked to the edge of the pool with his partner, the British cave diver Phil Short, and they put on their scuba rebreathers, masks, and fins. They’d spent the past two days on a platform suspended above another sump, rebuilding their gear. Many of the parts had been cracked or contaminated on the way down, so the two men took their time, cleaning each piece and cannibalizing components from an extra kit, knowing that they’d soon have no time to spare. The water here was between fifty and sixty degrees—cold enough to chill you within minutes—and Gala had no idea where the pool would lead. It might offer swift passage to the next shaft or lead into an endless, mud-dimmed labyrinth.

The rebreathers were good for four hours underwater, longer in a pinch. They removed carbon dioxide from a diver’s breath by passing it through cannisters of soda lime, then recirculating it back to the mouthpiece with a fresh puff of oxygen. Gala and Short were expert at managing dive time, but in the background another clock was always ticking. The team had arrived in February, three months before the rainy season. It was only mid-March now, but the weather wasn’t always predictable. In 2009, a flash flood had trapped two of Gala’s teammates in these tunnels for five days, unsure if the water would ever recede.

Gala had seen traces of its passage on the way down: old ropes shredded to fibre, phone lines stripped of insulation. When the heavy rain began to fall, it would flood this cave completely, trickling down from all over the mountain, gathering in ever-widening branches, dislodging boulders and carving new tunnels till it poured from the mountain into the Santo Domingo River. “You don’t want to be there when that happens,” Stone said. “There is no rescue, period.” To climb straight back to the surface, without stopping to rig ropes and phone wire, would take them four days. It took three days to get back from the moon.

Talking to kids about tragedy a tough task for parents

That's what I thought, and what many parents across the country said on social media following a stabbing rampage at a Pittsburgh-area high school on Wednesday.

The difference this time?

The suspect allegedly used two knives instead of a gun to attack his 20

victims, leaving several with critical injuries. Thankfully, they're

expected to survive, doctors said.

Fort Hood. Aurora. Sandy

Hook. Boston. Washington, D.C. Now, Murrysville, Pennsylvania. Another

mass tragedy filled with incomprehensible injury, nonstop news coverage

and a major question for parents: What do we tell our kids?

Last year, that question

was even more difficult for parents in the Washington area since their

children -- from elementary school age on up -- were likely to hear

about the Washington Navy Yard attacks that unfolded in their backyard

and left 12 people dead, as well as the gunman.

After that shooting,

Jessica McFadden, a mom of three who lives just outside Washington, said

she'd be taking her cues from her children about what to say and when.

At the same time, she said she would try to ensure that she and her

husband were the first sources of information for their eldest, a

9-year-old son.

"He's going to hear about

it, and I don't want him to be scared or to feel as if his world is

insecure if he hears about it from kids on the bus," said McFadden, who

founded the blog A Parent in Silver Spring.

"So we will be talking

about it with him; we will talk about how his school has great safety

procedures, how my husband's office has good safety procedures, how our

neighborhood is safe, that this isolated incident shouldn't make us more

fearful in our day to day," she said.

Sadly, McFadden knows

this from experience. A few years ago, McFadden's husband worked inside

the Maryland headquarters for Discovery Communications, where a man armed with a gun took three people hostage before police shot him to death.

"We had to talk about it

because other adults that came into our family's sphere were talking

about it, and so we wanted to make sure that we were the sources for the

children's information so that they weren't overly scared hearing about

it kind of second hand," she said.

Stephanie Dulli, who

lives in Washington with her two boys, ages 2 and 5, initially said she

didn't have any plans to tell them what unfolded. "It would accomplish

nothing but creating anxiety, especially for my eldest," said the host

of the blog Stephanie Says.

But there will come a

day when her boys are older, when sadly, another tragedy strikes and

when she'll definitely have to talk with them about it. It's not an easy

conversation for any parent, but for Dulli, it will be exponentially

harder.

Her father was murdered when she was around the same age as her 2-year-old.

"I guess I can only try

to do what my mother did. No matter how terrified or scared she was, she

never let it affect me," Dulli said. "I will try to do the same. To

explain what happened as clearly as I can, reassure and then show by

example that we just have to keep going. I may be terrified to let my

child go on the overnight trip, but he will never know that."

Reassurance is one of

the most important things parents can provide children during a time of

tragedy, when they fear it could happen to them, said Dr. Glenn Saxe,

chairman of the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at NYU's

Langone Medical Center.

"The first kind of

thought and feeling is, 'Am I safe? Are people close to me safe? Will

something happen? Will people I depend on protect me?' " said Saxe, who

is also director of the NYU Child Study Center.

"You want to be assuring

to your child, you want to communicate that you're ... doing everything

you can do to keep them safe," Saxe said. "You also want to not give

false assurances, too. And this is also depending on the age of the

child. You have to be real about it as well."

Sarah Grosjean, who

lives in Leesburg, Virginia, about 45 minutes from the Washington

tragedy, hoped to arm her 5-year-old daughter with information when she

talked to her.

"I want to be able to

make sure my daughter knows, in the event she's ever in something like

this ... how would she react? Would she know what to do?" said Grosjean,

founder of the blog Capitally Frugal,

who said she'll be emphasizing how her daughter should listen to the

police or teachers in case of an emergency when her mom isn't around.

Saxe said there are "no

hard and fast rules" on the right age to talk to kids about tragedies.

He said parents should take into account whether they think their kids

will have heard about an event, but -- especially for middle and high

schoolers -- parents should bring the subject up.

"I think the most

important thing is that the parent communicates a willingness to talk

about this, an openness about it, that parents are really attuned to

where their children are in this, even just asking a general question,

'Have you heard about this?' and see where your kid goes with that,"

Saxe said.

Parents should also be

mindful of what images their children are seeing on the news and make

sure even older ones, who may be watching the nonstop coverage, aren't

"flooded with images ... without any attempt to help make meaning for

them or bring perspective to it because that could be very difficult,"

Saxe said.

McFadden said she kept

the television off immediately after the Navy Yard shootings, but

followed the latest developments via social media on her laptop. She

knew she would be only so prepared when she ultimately had the

conversation with her kids.

"One of the biggest questions children ask is why," she said, "and that's something that we can't answer."

________________________________________________________

Report looks at whether millennial moms are more traditional, happier

Should a mom choose to

work, her children will be fine as long as there's a good child care

situation in place. You know the mantra, "happy mommy (who wants to

work), happy baby."

Based on that thinking, I have to say I was fairly blown away when I read one of the top findings of a new report by Working Mother Media,

which examined the attitudes of millennials (born 1981 to 2000),

Generation Xers (1965 to 1980) and baby boomers (1946 to 1964).

Millennials scored

highest, over Gen Xers and baby boomers, when asked whether they believe

one parent should stay home to care for the children: Sixty percent of

millennials said yes, vs. 55% for boomers and 50% for Gen Xers.

What? Are we moving in

the wrong direction here, ladies? Are we harkening back to an "Ozzie and

Harriet" time when mom stayed at home, dad worked, and that was the

complete family story?

Jennifer Owens, editorial

director of Working Mother Media, says no. She points to what else the

millennials said in the survey of more than 2,000 moms and dads: that

both parents should make a significant contribution to the household

income, that mothers and fathers should share equally in daily household

activities and that a mom who works outside the home sets a positive

example for the children.

"I think many men and

women want ... the ability to step in and out of their careers and not

be stigmatized for it, and I think the millennials are saying this,

too," said Owens, who notes that most millennials currently have

children who are younger than those of of Gen Xers and baby boomers.

"Many men and women want

to stay home with that little guy in the first years," she added.

They're saying "somebody should be home with that little tiny baby, but

they do want a career."

In conversations with

millennial moms across the country, I was struck by how much they

believe the decision to work or stay at home is personal rather than

political, how many would stay at home if they could and how they don't seem to feel the pressures of feminism driving their decisions. They are charting their own course.

Aliah Davis-McHenry, 33, president and chief executive officer of her own public relations firm,

has two sons, ages 8 and 11. She's done it all: stayed at home when the

boys were young, worked part-time and consulted during their preschool

years and now works full-time from home, which means she can be there

when her sons get off the school bus.

"I feel like it's a very

personal decision," Davis-McHenry said. "In a perfect world, with all

the variables being aligned, who wouldn't want to be home every day? ...

But that's not the world we live in."

Miriam Lane, 25, who

works in sales for a television station in Huntsville, Alabama, says she

or her husband could probably stay home with their 2-year-old daughter,

but that wouldn't support the kind of lifestyle they want for their

family.

"I think it's great if a

parent can stay home," Lane said, "but there are a lot of situations

where it's just not feasible to be able to do that. I know specifically

in our situation, we do have to have both parents working to be able to

afford beyond just our basic needs."

Christine Esposito's

feelings are influenced by her own mom, who didn't work. "I always had

the image of me being like her and staying home," said Esposito, 30, who

works in the e-learning field in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, and has a

2-year-old daughter.

"But I really feel like

things have changed a lot," she added. "I don't want to stay home and

never be able to go out to dinner and never be able to go on vacation."

For Patricia Downs, a

31-year-old mom with a 2-year-old boy in day care, the issue is

clear-cut: She thinks a parent should be home with the child, and she

wishes it could be her.

"I think that's the best

thing for my child," said Downs, an account manager in the cosmetics

industry in Stony Point, New York. "I feel like he misses out on time

with myself, my husband. ... There are times he needs Mommy, and I'm

just not able to go."

I wondered whether the

views of millennials on this question of whether one parent should be

home with a child were influenced either by their own upbringing as

children of dual-income Gen Xers and boomers or by the experiences of

people they know.

Meghan Lodge, 24, whose

daughter is just 8 weeks old, said her views are definitely shaped a bit

by the childhood of some of her friends.

"I have some older

friends who ... had to stay in day care, or they had to come home by

themselves" when they were older, Lodge said. The Thomasville, Georgia,

woman believes that one parent should stay home with the child if they

can afford it. "I mean, they turned out fine, but they always talked

about how much they wished they had more time with their parents."

Beyond the question of

working versus staying at home as parents, millennials told us something

else in this survey: that they are a whole lot happier than previous generations

(PDF). They reported more satisfaction with their jobs, their family

finances and their relationship with their partners than Gen Xers and

baby boomers.

"I think we're more

motivated towards achieving satisfaction and balance," Davis-McHenry

said. "I don't think it's only about making money. I believe it's more

about fulfillment: feeling like we're making a difference and making

sure that everything from home to work, those needs are being satisfied,

and I think that's what's making us happier."

Many millennial moms say

they are thankful to the women who came before them, the Gen Xers and

baby boomers, who broke down barriers, allowing them to make the choices

they want to make for their lives. But at the same time, they don't

seem to feel any of the pressures of fulfilling anyone's expectations

other than their own.

"We do things more

according to what we see fit for our family, what's best for the family,

rather than what other people think about it," Lodge said.

Owens, of Working Mother, believes that this optimism on the part of millennials has definite implications for the workplace.

"They're going to demand

more. They're already asking questions about the 24/7 always on (work

life)," said Owens, herself a Gen Xer. "They're asking for flexibility

already as a given, and you know what, they're not even asking for it.

They just expect it. And amen to them."

From this Gen Xer as well, amen indeed!

____________________________________________________

Do opposites really attract?

As a culture, we seem to

love saying that, and when opposites do attract -- whether in movies or

in real life -- we're fascinated. The rich sophisticate and the

working-class hero. The popular guy and the nerdy bookworm. The dwarf

and the elf. When romance blossoms between a seemingly mismatched pair,

we root for them. We wait to see what kind of fireworks will happen, and

hope their relationship will succeed. It's like a fairy tale: Two

totally dissimilar people celebrate their (extreme) differences and live

happily ever after. True love wins!

upwave: How to be lucky in love

The verdict: Generally speaking, opposites don't attract at all

Put simply: We like

people who are like us. And the more we have in common with someone, the

more likely we are to get along. (Sorry to burst your bubble.)

Sure, the idea of two

incredibly different people being able to find love is cool and

spirit-lifting. It makes for great movies and books and daydreams. But

in real life, mismatched couples rarely last. "Based on what research

evidence shows, similar people are more likely to get together in the

first place -- and are also more likely to find satisfaction in their

relationship," says William Ickes, distinguished professor of psychology

at the University of Texas at Arlington and author of "Strangers in a

Strange Lab." "The theme is that love is such a powerful force that it

can transcend all those differences. What we know in real life -- after

the honeymoon, or maybe sometimes during the honeymoon -- is that all

those differences suddenly emerge and foretell doom for the

relationship."

That doesn't mean you

have to be utterly identical to your partner, says Sean Horan, an

assistant professor in relational communication at DePaul University.

Successful couples can be different in some minor areas. But most people

who have great relationships share similar backgrounds, core values and

attitudes about what they like and dislike, he says.

Still not convinced?

Consider your BFFs. "If you look at who your friends are... they're more

similar to you than different," says Horan. "In general, humans are

uncomfortable with uncertainty. Similarity allows us a certain level of

predictability. [When situations occur], you can generally predict how

your partner will react." And that's a comforting thing.

One case where opposites

really don't attract, according to Ickes? Introverts vs. extroverts.

Through his research, he has found that two introverts get along fine,

two extroverts get along fine, but an introvert rarely gets along with

an extrovert. "If you think about it, it makes sense," he says. "The

extrovert is going to want to go out to parties and events, spend time

with other people and socialize a lot. The introvert isn't going to want

to do that. It's going to affect how they spend their time."

_________________________________________________________

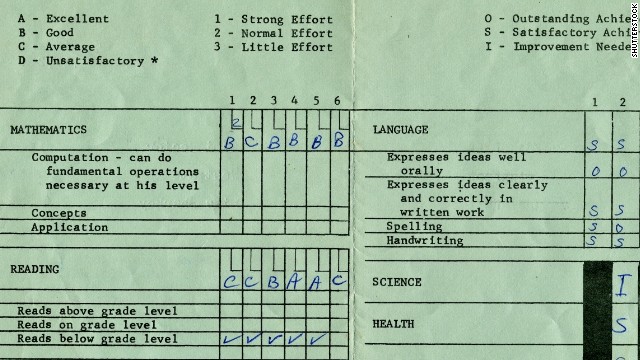

Ditching letter grades for a 'window' into the classroom

Sometimes, it's a picture

from 7-year-old Serenity's writing journal, with a line or two of

feedback from her teacher; or, it could be a video of Serenity singing

in music class.

The messages come at

least once a week, sometimes more, and provide Wolfram with more than

just a brag book of images. It's real-time insight into her daughter's

learning, enabling her to think ahead about how she can help Serenity at

home.

The messages started

going out to some parents at Georges Vanier Elementary School in Surrey,

British Columbia, in fall 2013 as part of a pilot program. The school

wants to make communication between parents and teachers more detailed,

frequent and collaborative.

Because Wolfram is

getting frequent updates about her daughter's educational highs and

lows, there are no surprises come report card time. Eventually, the

district is hoping to phase out periodic report cards in favor of

regular, descriptive communication and a year-end summary or portfolio

review, Surrey school district Superintendent Jordan Tinney said.

We believe traditional report cards are highly ineffective in communicating to parents where their children are in learning.

"We're trying to boil it

down to what do parents really want and need to know about a child's

progress in school? How can we give parents a window into class?" Tinney

said.

"We believe traditional

report cards are highly ineffective in communicating to parents where

their children are in learning. If we can communicate this learning

routinely to parents, then we see the need for report cards and the

stamp of letter grade going way down."

Schools around North

America are trying to replace traditional report card grids of letters

and numbers with descriptive feedback about students' mastery of topics.

Rather than a series of cumulative scores in each subject based on a

mashup of tests, homework, extra credit and behavior, schools are trying

to show how well students understand core concepts -- and involve

parents more in the process.

In the education world,

it's often called standards-based grading. It's become the norm at most

elementary schools, and it's gaining momentum at the secondary level.

Still, it can be a

struggle for parents who remember their own semester report cards and

the easy comparisons made between As, Bs and Cs or number scales.

Others, like Wolfram, like the change.

"It's been helping me

feel like I'm more connected to my daughter and her classroom," Wolfram

said. "By visually seeing my child's work, I can see what the teacher

means by 'She's not writing enough,' and work with the teacher to fix

the problem."

Separating achievement from behavior

The philosophy behind

standards-based grading is generally consistent from school to school,

but it can look a lot different in practice.

At Georges Vanier and

other Surrey elementary schools, it means abandoning letter grades for a

color-coded sliding scale with cues like "approaching expectations" and

"meeting expectations." Nearby elementary schools serving the Maple

Ridge and Pitt Meadows communities rank student comprehension as

"emerging," "developing" or "applying," and hold "student-led,"

in-person reporting conferences twice a year instead of sending home

formal report cards.

A new grading system in Virginia Beach, Virginia, elementary schools, marks students on a range from "advanced proficient" to "novice" in each subject's standards.

In Oregon, a new law

says schools can use letters or numbers to assess students, but the

grades must be based solely on academic performance. Those marks will no

longer consider whether an assignment was turned in late or if a

student talks in class.

Proponents of the new

systems believe that traditional grading leads to inflated marks for

students who behave well in class, even if they don't have a strong

grasp of concepts -- and lower grades for those who understand ideas but

arrive late or fail to turn in homework.

Flaws in traditional grading come from outdated and inconsistent notions about its purpose, said Ken O'Connor, an education consultant who advocates for standards-based grading.

"They give the community

the wrong message of what school's all about, that it's about the

accumulation of points, when we should be doing everything to make clear

school is about learning," O'Connor said.

But what's popular for elementary-age students can be a tougher sell in middle and high school.

Parents and teachers

become less willing to abandon letters and numbers as students prepare

to apply for college, O'Connor said. But even within the same school,

different teachers might determine grades in inconsistent ways, he said.

O'Connor argues that

numbers and letters can serve a purpose -- as long as they're buttressed

by ongoing communication of a student achievements.

"Report cards are a

permanent record -- they're helpful to provide a summary of student

achievement every year as part of a communication system, but it's not

right to think they're the be-all-and-end-all," he said.

Some schools are

compromising at the middle and high school levels by implementing

standards-based learning that still incorporates letter and number

grades.

At the Solon Community

School District in Iowa, older students still receive letter grades, but

parents hear more often from teachers and there's a fresh focus on

priorities, said Matt Townsley, the district's director of instruction

and technology.

Solon schools are in the

second year of implementing standards-based learning for kindergarten

through 12th grade. In the past, teacher comments might be jotted on the

pages of a test or scribbled in the margins of a term paper. In the new

system, detailed feedback is available digitally, and it's the focus of

periodic parent-teacher discussions and student evaluations. Plus, it

helps to use those tests and term papers as evidence to support student

assessments.

"We felt eliminating

letter grades would be too much at once," he said. "But we know

homeschooled children who often don't get letter or number grades make

it into college each year. We just need to do the research on our end

and figure out how to make the college seamless transition for students

and be able to assure parents."

No parent support? 'Dead in the water'

The schools serving

Maple Ridge and Pitt Meadows in British Columbia began developing a plan

to eliminate letters and numbers from kindergarten through seventh

grade in the 2010. Parental involvement was essential to taking the plan

live district-wide in fall 2013, acting Assistant Superintendent David

Vandergugten said.

"We realized early on that if you don't have parents on board, you're dead in the water," he said.

All schools in British

Columbia stopped using letters and numbers in kindergarten through third

grade classrooms years ago, and more recently in grades four to seven.

The district interviewed parents and asked them to evaluate templates, leading to the new system in which students and teachers fill out an assessment sheet that measures their competencies at their grade level.

In the first two terms

of every school year, students lead a conference with their parents and

their teacher to discuss the evaluation. In the third term, the student

and teacher work on the evaluation together before sending it to parents

at the end of the school year. That final evaluation goes into

students' permanent records.

Parents of students in

grades four to seven can still request letter grades. But Vandergugten

said the number of parents who requested them went down after the first

term.

"The face-to-face

process is so powerful that we're finding once parents go through it,

they understand what we're trying to accomplish," he said, claiming a

97% participation rate among parents in the student-led conferences.

At Georges Vanier

Elementary School in Surrey, students still received report cards in the

first term. But by using notes she'd been taking throughout the year,

second-grade teacher Wendy Hall said she spent far less time preparing

them.

Before, she said, she would jot notes on slips of paper and rarely reached out to parents. Newly equipped with an iPad and FreshGrade assessment software, she typically sends parents one to three individualized updates each week.

Parent Krista Wolfram

says she is already seeing the benefits for her daughter. When Hall told

Wolfram that Serenity was struggling to write about her favorite

superhero, Wolfram immediately knew it was because Serenity didn't have

one -- she's more interested in fantasy stories and dragons.

She and Hall came up

with the idea to provide alternate writing topics for students, and that

improved Serenity's performance, Wolfram said.

"She went from complete

fail in the topic, which I wouldn't have known about until report card

time, to a complete pass by report card time, which is just so exciting

for a parent," she said.

Susan Taylor, whose son

is also in Hall's class, used the evidence to improve her son's

penmanship. Taylor said she loves the window into her son's classroom

because he rarely offers up information when she asks him.

"It gives me the ability

to do more directed questioning instead of 'How was your day?'" she

said. "I have a better take on what's happening."

Still, the transition isn't entirely smooth. Not all the elementary school teachers use the software with the same frequency.

An older son in eighth

grade is adjusting from receiving letter grades in seventh grade to a

new sliding scale that says he's approaching, meeting or exceeding

expectations.

Meanwhile, Taylor says

she wouldn't want to give up letter grades for her 12th-grade son. He's

applying to post-secondary schools that ask for GPAs and reports in

numbers and letters. Still, she wishes she received regular updates on

his progress, and that he'd have a digital portfolio of work like her

younger children will.

"If they could find a way to dovetail the two systems, that would be ideal," Taylor said.

Reconciling multiple

systems -- and levels of comfort among educators -- are some of the

biggest challenges schools face, Georges Vanier Elementary School

Principal Antonio Vendramin said.

And, that's OK, he said. Changes take time.

"As long as we're

getting into the habit of communicating student learning on an ongoing

basis, we're on the right track," Vendramin said. "Scales, letters and

numbers are only as good as the meaning you give them."

______________________________________________________

Using tablets to reach kids with autism

Two 5-year-old boys, one with autism, were having some friendly

playtime when they had a communication breakdown. One boy didn't respond

to the other and walked away. The ignored kid got frustrated and pushed

over a small staircase, causing the first boy to fall.

Two 5-year-old boys, one with autism, were having some friendly

playtime when they had a communication breakdown. One boy didn't respond

to the other and walked away. The ignored kid got frustrated and pushed

over a small staircase, causing the first boy to fall.

Their speech therapist, Jordan Sadler, decided to address the issue by recreating it in an iPad app called Puppet Pals.

She restaged the scenario as a movie, even taking photos of the room

for the background and of the kids for the characters. Using the app to

show an instant replay of the scuffle, Sadler and the kids identified

what went wrong and then recreated the scene, this time making better

decisions.

Creating custom stories

to help kids learn communication skills or understand complex situations

is just one of the ways parents, therapists and educators have taken

advantage of tablets to work with kids with autism.

Tablets as tools, not miracles

When the iPad made its

debut in 2010, it was hailed as something of a miracle device and there

was a rush among parents of kids with autism to get the $499 gadget.

"They were throwing them

at their kids expecting miracles, but it didn't happen. The reason is

they are tools, not miracles," said Shannon Rosa, an author and former

educational software producer who has written about using tablets with

her own son, Leo, who has autism. "I think a lot of parents now are more

realistic about the level of support that is needed to help kids use

them."

Four years later, tablets

still play a big role in the autism community. But the expectations for

the technology have come down to earth a bit. Now app creators, autism

educators and parents are exploring new ways of using tablets and apps

to work with the 1 in 68 kids in the U.S. with autism.

They've had time to

discover what works best for kids with autism when it comes to tablets.

The uses vary from child to child, and often the best apps aren't even

created with kids with autism in mind.

Rosa said it allows her

son, now 13, to think visually, to interact with content directly

without the cognitive hurdle of a mouse, and it breaks complex concepts

up into more easily understandable chunks. Siri is even helping him with

articulation.

The tablet has also

given him more independence. Leo used to have a really hard time

figuring out what to do with himself when someone didn't structure his

day for him. Now he can use the iPad on his own and have a good time

independently. Rosa, though, like many parents, is careful about letting

her son have too much screen time.

Sadler gives iPad

workshops all over the country, teaching people about the most effective

ways to use the device. She tries to move parents away from using

mobile devices as a reward, letting children just play games or watch

YouTube videos. She encourages parents to seek out dynamic apps that can

help with the core challenges of autism while also being fun.

"It's really important

to learn and improve social communication skills," said Sadler. "But it

has to be something that grabs them."

Mixing laughter and lessons

Flummox and Friends

is a hybrid of an app and a TV show for kids on the autism spectrum

that seeks to be more than just educational or just entertaining.

Released on the iPad in April, it's a live-action comedy show that aims

to educate children by being entertaining, not condescending.

The main characters are

inventors and their friends, and they're written so children with autism

can relate to them. They find themselves in tricky situations that they

need to invent their way out of. The idea is to teach social and

emotional skills through funny plots.

Using pop-up prompts,

the app sets up situations that kids with autism may have trouble with,

such as anticipating someone else's perspective, managing someone else's

emotions, and being flexible instead of being rigid. A scene might show

some of the ways communications can break down, then walk the viewer

through ways to fix the problem.

"Typically, how this

stuff has been taught is giving kids scripts saying, 'Say this when you

meet someone,'" said the show's creator, Christa Dahlstrom. "It's kind

of suggesting (they) aren't doing this right and need to be normal."

Flummox and Friends is geared more toward acceptance, and Dahlstrom is interested in working with

the kids whose minds are wired differently, not correcting them. The

app reflects a larger shift in the community away from "fixing" autism

to accepting and embracing it.

"(Technology) can make a

profound difference to the kids with autism, but it's not like it's a

cure for it," Dahlstrom said. "You've got to stop thinking of this as a

parental problem."

Dahlstrom, who has

worked in learning design her whole career, has observed firsthand how

her own 10-year-old son with autism learns and what he struggles with.

She noticed that he tends to open up when people are laughing, having

fun and quoting TV shows. After realizing comedy could be a great tool

for reaching children with autism, she started a Kickstarter campaign to

raise money for the first Flummox and Friends episode.

The show is meant to appeal to 6- to 12-year-olds, which is a slightly older audience than most autism apps.

"In terms of apps for

kids with autism and special needs, there's a lot of stuff for

preschoolers. There's not as much when you start going up to an older

audience, especially when it comes to social skills," she said.

The multi-purpose rectangle

Tablets have replaced a

number of other tools for parents and educators, including handmade

visual aids, expensive communication devices and, increasingly, TVs.

The gadgets are a more

affordable alternative to the dedicated augmented-communication devices

some nonverbal kids use to communicate. Those can cost between $6,000

and $8,000, but with a tablet, kids who aren't speaking can use

voice-output apps instead.

Teachers and therapists

no longer have to slog through the mundane task of making visual tools.

Making cue cards is a common technique when working with nonverbal

children, but it requires taking photos, uploading them to computers,

printing them out, laminating them, adding some velcro and sticking them

on boards. The addition of a camera in the second version made the

process even easier.

"It really sort of took

us out of the dark ages in terms of how quickly we could make visual

supports for the kids and how quickly kids could access what they

wanted," said Sadler.

One thing that makes Flummox and Friends unusual is that it is a fully scripted TV show delivered as an app.

Tablets give kids much

more control than they have with a TV. They can hold a tablet in their

hands and have a more intimate experience with a story or game. Watching

clips and shows repeatedly is common among children with autism, and

with tablets they can rewatch favorite segments over and over.

"We've really started to see children's media migrate from the TV screen to the iPad "